In Virginia, there has been an increase in state and local law enforcement diverting time and resources away from public safety and enforcing Virginia law to support, or even act as, federal immigration enforcement agents (e.g., ICE).

We have seen this happen in other states throughout the US, too, including detaining people strictly for civil immigration purposes and without any valid reason under state law and using access to protected driver information and other confidential data to assist with civil immigration enforcement. These formal agreements can also enable state and local law enforcement agencies to perform many of the duties of an ICE officer, including arresting and detaining people they believe to have unlawful immigration status, which carries increased risk of discrimination, given the extremely minimal amount of training they receive.

These agreements purport to give law enforcement powers that in many ways exceed or conflict with Virginia’s state law and constitution. These vast new powers, involving one of the most complicated areas of law, are exercised with the equivalent of only 40 hours or less of online training.

Since early 2025, LAJC has been investigating the many ways that state and local law enforcement and jails have been diverted away from their public safety mission to join ICE in its rush to arrest, detain, and deport millions of aspiring Americans. This investigation has primarily but not exclusively focused on so-called “287(g) agreements,” after the section of the federal Immigration and Nationality Act that references them—and sent over 50 Virginia Freedom of Information Act (VFOIA) requests to local sheriff’s departments and state law enforcement and correctional agencies across Virginia.

Our investigation found a significant number of state and local agencies that are deviating from their traditional missions, committing resources and assuming risk, setting aside public safety concerns and the constraints of the laws of Virginia in support of an effort that terrorizes our immigrant neighbors. Often, these agreements have been created in secret, and agencies were reluctant to share information about them in response to our requests, a significant number telling us they were not allowed to respond to our requests at the direction of ICE.

Below, you can learn more about what 287(g) agreements are, where they are currently in place in Virginia, and summaries of what we have learned from our research. You can also access many of the source documents we obtained through our VFOIA requests.

This information is based on responses to public records requests received from June to December 2025 and is subject to change. LAJC will update this analysis and the document bank as our investigation continues.

Governor Spanberger signed an Executive Directive to end all statewide 287 (g) agreements with ICE. Read LAJC’s statement on this action here: Statement on Ending Statewide 287(g) Agreements

Governor Spanberger rescinded the previous administration’s executive order (EO 47) that had directed the Virginia State Police and Virginia Department of Corrections to enter into contracts with ICE and encouraged local law enforcement to collaborate with ICE. The state has also subsequently signed additional contracts with ICE that are not prescribed in the Executive Order, such as with the Department of Wildlife Resources. All state and local agreements remain in force until terminated by one or both parties. There has yet to be evidence that any contracts or collaborations between ICE and state law enforcement have ended.

What is 287(g)?

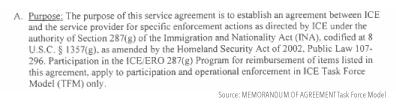

Under the 287(g) program, ICE claims it can delegate to specific employees of state and local agencies, usually law enforcement, the authority to act as independent federal immigration officers under that agreement. These duties are carried out with limited oversight by ICE, and with 40 hours or less of online training in immigration law and enforcement. A 287(g) agreement only applies to the specific employees who have been nominated, trained, passed an exam, and are then certified by ICE.

The WSO model involves state and local law enforcement in serving administrative civil immigration warrants in their agency’s jail. The contracts with ICE purport to give such jails legal authority to hold people subject to these warrants an additional 48 hours after they were otherwise supposed to be freed, even though Virginia law does not authorize this. This means that when a person held in a local jail is targeted by ICE, the jail will detain them after their release date to transfer them to ICE custody for removal proceedings. The WSO model only requires the equivalent of 8 hours of online training.

Unlike the WSO model, the JE model purports to allow jail personnel to act on their own without ICE, holding people for up to 48 hours based on their own judgment of whether someone is violating civil immigration laws. The JE Model contract tells jail personnel they have the power to identify people they believe to be noncitizens held in prisons and local jails, interrogate them about their immigration status, place them into removal proceedings, detain them beyond their release date, transport them to immigration detention, and other things. This means that individuals are held past their release time, without a valid judicial warrant or any other lawful reason. The Jail Enforcement Model only requires the equivalent of 20 hours of training.

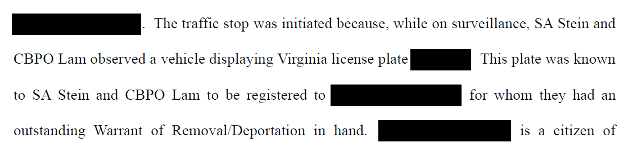

Unlike the WSO and JE models, which focus on people who are in jail or already involved in the criminal system, the TF Model applies to everyday policing. The TF Model turns your neighborhood police officer or state trooper into an ICE agent. Thus, instead of focusing solely on public safety and enforcing state and local laws, officers with little experience (as little as two years on the force) and the equivalent of just 40 hours of online training are expected to apply immigration laws in their everyday interactions. Most 287(g) agreements in Virginia are TF model.

Early versions of this model were so problematic, including serious civil rights abuses, that President Obama ended the program. The Task Force Model was not used during the Trump administration’s first term, even though it was available, due to a lack of interest from state and local law enforcement. This model is coming back to use only now.

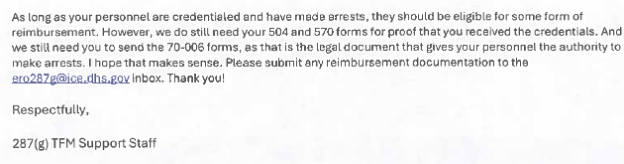

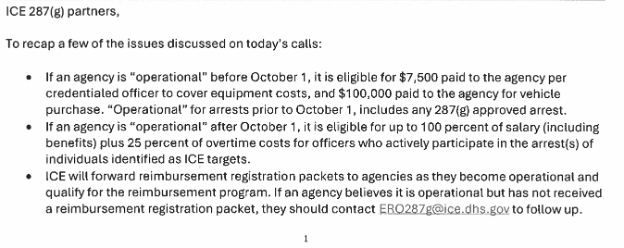

As of November 2025, many TF model agencies have signed a second ”service agreement” in order to receive reimbursement for the time they spend. Each agency must file a worksheet with ICE each month, detailing the time and activities they spent on immigration enforcement rather than carrying out their public safety mission. This has already led to some civil immigration arrests being made directly by local law enforcement without direction or supervision by ICE.

Where are 287(g) agreements in place in Virginia?

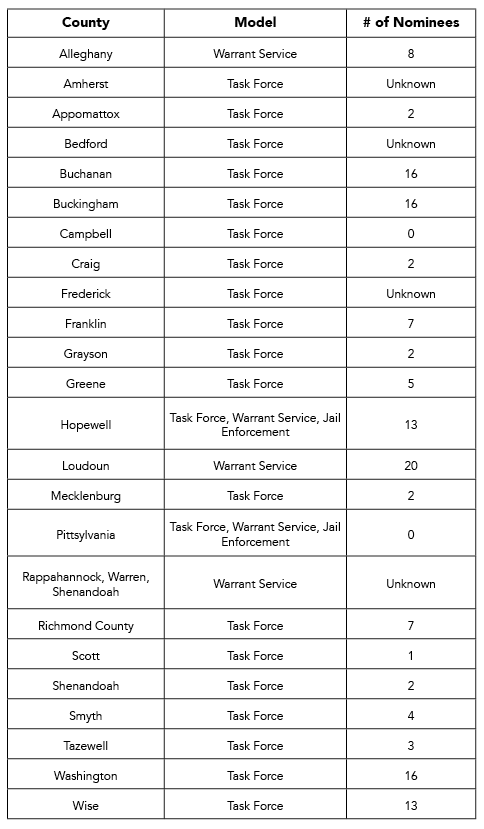

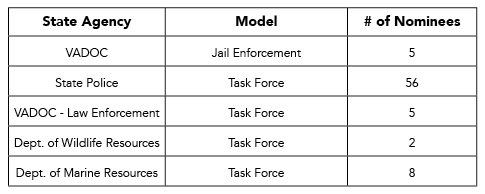

Explore the map below to see which counties and government agencies from the 50 we requested information from currently have agreements or have pending agreements, and the number of staff they have nominated to participate in the agreement.

map last updated 1/5/26 – Click the icon on the top left to see key and other information

287(g) in Virginia, by the numbers

32*

287(g) agreements in total

4*

state agencies:

Virginia State Police, Virginia Department of Corrections, Virginia Department of Fish and Wildlife, Virginia Department of Marine Resources.

4

jails:

Alleghany, Loudoun, Rappahannock / Warren Shenandoah Regional Jail, Southwest Virginia Regional Jail

23

local sheriffs:

with police powers.

3 Jail Enforcement Models – 6 Warrant Service Officer Models – 24 Task Force Models

As of December 29, 2025, at least 223 state and local personnel nominated to act as immigration enforcement, at least 157 of which have been certified.

2 “security resource officers”

embedded in public schools [Buckingham and Washington Counties]

1 “behavioral health advocate”

[Washington County]

see update re: Governor’s order to end statewide 287g agreements

Who pays for the time law enforcement spends working under 287(g) agreements?

Until recently, work performed under these agreements was almost entirely funded by the law enforcement agencies themselves. This meant that state and local taxpayers were directly footing the bill for work that had nothing to do with public safety. However, a bill passed by Congress in 2025 made federal funding available for 287(g) activities.

This does not fix anything – it only makes the problem worse. The federal funding provided under 287(g) service agreements is only paid based on detailed proof of the time and resources law enforcement spent on doing work for ICE, rather than the actual public safety work that state and local law enforcement exist to do. This money creates a powerful financial incentive to further pull officers from what the law and electorate need them to do, and instead act on an agenda established by ICE. Law enforcement decisions should never be based on an “eat what you kill” basis.

What are some of the other agreements between ICE and state / local law enforcement?

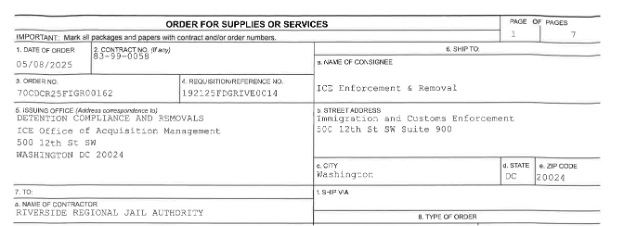

The other main type of agreement is an IGSA, which stands for “intergovernmental service agreement.” IGSAs are used any time the federal government contracts with another part of federal, state, or local government for services. The relevant IGSA here involves ICE or another federal agency contracting with state and local prisons and jails to use beds and administrative space for civil immigration detention and processing.

Theoretically, ICE could draft new contracts for detention. However, they often use modifications of existing contracts between jails and other federal agencies, such as a prior contract for holding people in state jails for federal criminal issues.

It is difficult to know exactly how many IGSAs or similar agreements might currently be in place in the Commonwealth, but two examples are Riverside Regional Jail and Southwest Regional Jail.

The Riverside Regional Jail has detained thousands of people for short-term detention since July 2025. People held at Riverside often disappear from systems used to locate detained people and have great difficulty contacting their family or their attorneys. Our investigations have found most of the people who are held at Riverside do not have any criminal history, and in some cases don’t even have a pending removal case with ICE. Riverside has also begun holding women, which is exceedingly rare. According to Riverside’s own jail board minutes, over 50% of the jail’s projected revenue for 2026 will now come from ICE detention.

Are there ways that state and local law enforcement have worked with ICE without a formal agreement?

It is not uncommon for local and state law enforcement to collaborate with ICE informally. For example, LAJC’s investigation has turned up several situations where jails have detained or transported people “as a courtesy” for ICE, in violation of Virginia law.

State and local law enforcement appear to have shared sensitive and legally protected information with ICE, outside of their public safety mission. Since 2021, DMV information that connects to someone’s personal identity, address, and other personal information may not be used for civil immigration enforcement. Not only is it against the law for the DMV to provide this information for this reason, anyone else who gets the information for another legitimate reason may not share it for this purpose. However, despite the promise of the law, DMV data appears to have been used for immigration enforcement purposes.

Do state and local agencies need to provide information to the public about their participation in these agreements?

Public entities like state agencies, sheriffs, and regional jails are required to follow state public records laws, like VFOIA. However, in our investigation, we found that several of these agencies at least initially refused to provide even basic information subject to disclosure under VFOIA, claiming that they do not have to follow state laws like VFOIA because they signed a contract with ICE. Sometimes this has even included a refusal to provide information to other people in government, like County Supervisors. In more than one case, LAJC was forced to go to the extraordinary lengths of preparing litigation in order to secure basic information about these secretive agreements.

287(g) agreements and IGSAs don’t just divert resources. They undermine public safety by weakening trust in the basic systems Virginians rely upon.

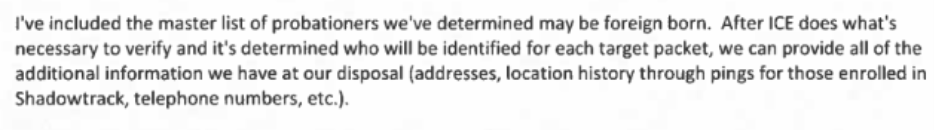

One of the most concerning examples of this is how the Virginia Department of Corrections (VADOC) supervised release system has been turned into a deportation surveillance service. VADOC has shared massive amounts of information about parolees and probationers, many of whom are attempting to comply with the terms of their supervised release.

VADOC has not just been sharing information with ICE about probationers and parolees themselves, but has also been sharing information about family members and friends who visit or communicate with loved ones who are incarcerated. This undermines public safety by disrupting the supportive networks that people who are incarcerated and on community supervision desperately need to navigate reentry. It also makes what is already a difficult situation for family and friends exponentially worse, by putting people under presumptive suspicion simply for offering what they can to support their loved ones.

Not only do these activities undermine VADOC’s stated mission of rehabilitation, but they also massively disincentivize voluntary cooperation with supervised release programs by penalizing compliance with the law—this puts all communities at risk.

For example, documents we received from the Department of Corrections show that information is being passed not only about immigrants who may not have permanent status, but also about people who “may be foreign born” — including US citizens.

When people in Virginia fear any interaction with law enforcement due to their immigration status, it harms both those families and the broader community. Families don’t seek out needed services, don’t report crimes witnessed or crimes they have experienced as victims to police, and limit their participation in their communities. This makes us all less safe.

Law enforcement priorities should be set based on the needs of state and local communities. Instead, under 287(g) and IGSA agreements, these agendas are now driven by federal priorities that do not factor in what Virginia communities want and need. This is especially true now, as the infusion of federal funds conditioned on detailed accounts of time spent carrying out ICE’s agenda create an eat-what-you-kill system that incentivizes pulling resources away from local concerns in order to bring in funding to the agency.

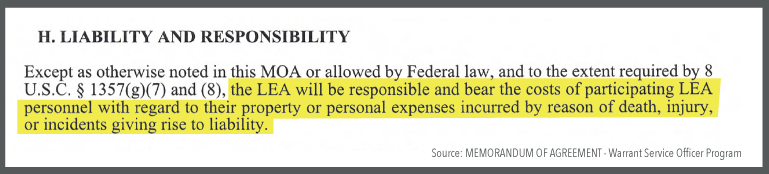

The lack of training on our complex immigration system and vital civil rights laws leaves 287(g) localities in a very risky place. In most agreements, the federal government offers no guarantee of support should an officer be caught violating the law in attempting to detain a community member for ICE. This leaves local governments at risk of lawsuits, costing taxpayers even more.

Caption: From the section on liability from the MOU between ICE and Allegheny County

This should concern law enforcement agencies, but also the insurance systems and ultimately taxpayers who will foot the bill for lawsuits. This is especially true because many of the things that 287(g) and IGSA agreements purport to allow are beyond what the Virginia Code and Constitution currently allows, which combined with the lack of training and support makes the risk of lawsuits very high.

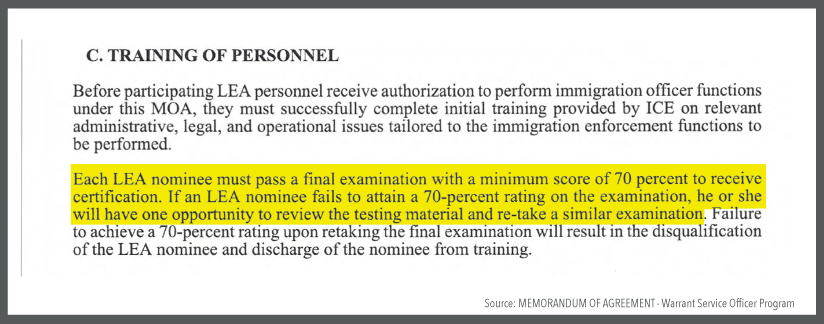

Officers who participate in 287(g) agreements receive shockingly little training in how to enforce immigration laws. ICE states on its promotional flyer for one of the 287(g) models that officers “…complete a 40-hour online course covering, among other things, scope of authority, immigration law, civil rights law, cross-cultural issues, liability issues, complaint procedures, and obligations under federal law.” One week of online training could only scratch the surface of immigration law alone, which is one of the most complex areas of law. Not only that, but officers only need to get a “C” on the final exam.

This is just part of the picture

While the VFOIA requests made by LAJC shed some light on how local and state law enforcement agencies are entering into formal collaboration with ICE, a number of our requests were denied.

In those cases, the localities often incorrectly claimed that ICE could prohibit the release of communications between ICE and the law enforcement agency, rather than comply with Virginia’s FOIA law by releasing all responsive documents in the localities’ possession not protected by FOIA. While we are working to educate those who were not fully responsive to what Virginia’s FOIA law encompasses, this is just another example of how ICE is hiding its activities from public scrutiny.

We want to hear from you

Did you, or someone you know, experience an immigration-related incident in Virginia with your local or state police? We are collecting stories and information to better understand how Virginia’s contracts with ICE are working and to limit local and state collaboration.

Your story

*Filling out this form does not mean that LAJC will represent you in any legal issue. While we can’t reply to everyone who fills out this form, we may reach out for more information on your issue. We will never share your name or contact information with any other party. By filling out the form, you agree to allow us to use aspects of your story in our advocacy, including on digital and print advocacy materials.

Information Accuracy and Completeness Disclaimer

The information in this web resource was compiled from public records obtained through public records requests. While we have made reasonable efforts to ensure accuracy, this information may be incomplete, outdated, or subject to change. Public records may not reflect the most current status of matters, and agencies may have updated their records since our requests were fulfilled. Users should verify any information they intend to rely upon by consulting the original source or contacting the relevant agency directly.

Legal Advice Disclaimer

This web resource and database is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The information presented here should not be used as a substitute for professional legal counsel. Each situation is unique, and laws vary by jurisdiction and change over time. If you need legal advice regarding your specific circumstances, please consult with a qualified attorney licensed to practice in your jurisdiction. Accessing or using this database does not create an attorney-client relationship between you and the Legal Aid Justice Center or any of its staff.